The Two Sides of Our Writing Brain: Supporting Student Writers in Process

Of all the things I’ve learned as a writing teacher, it’s that sometimes there are things we need to help our students release, things we need to help them let go of. One critical place to do this is in teaching students about the two sides of their writing brains: the composer and the editor.

Every time I assign writing, I make sure students know which part of their writing brains I’m expecting to see. Far too often we see writing assignments handed out with the expectation that the entire writing process happens, from start to finish, every single time. This doesn’t have to be the case! We can have students write to explore a thought, write to refine a thought, write to come up with a thought, or write to clarify a thought. When students are exploring, brainstorming, or even arguing something for the first time, they need the space to dump everything on the page. The engrained instinct, however, is for most students to start writing something and edit as they go. As a result, we have many students who are stuck staring at a blank page, turning in unfinished assignments, or constantly asking for sentence-by-sentence feedback from the teacher.

Let’s look at ways to show students and practice the two sides of their writing brain.

The Composer-Side of the Writing Brain

When we write, the composing side of the brain needs to be set free. If our students are paralyzed with what they’re supposed to do and hovering over the delete key more than the space bar, their ideas are going to stay trapped in their minds and never make it on to paper. When I define the composer-side of the brain, I let my students know that this is the IDEAS side. This is where we harness all of the messy ideas and get them out into the world.

In order to hone in on this side of the writing brain, here are two easy strategies to utilize in the classroom:

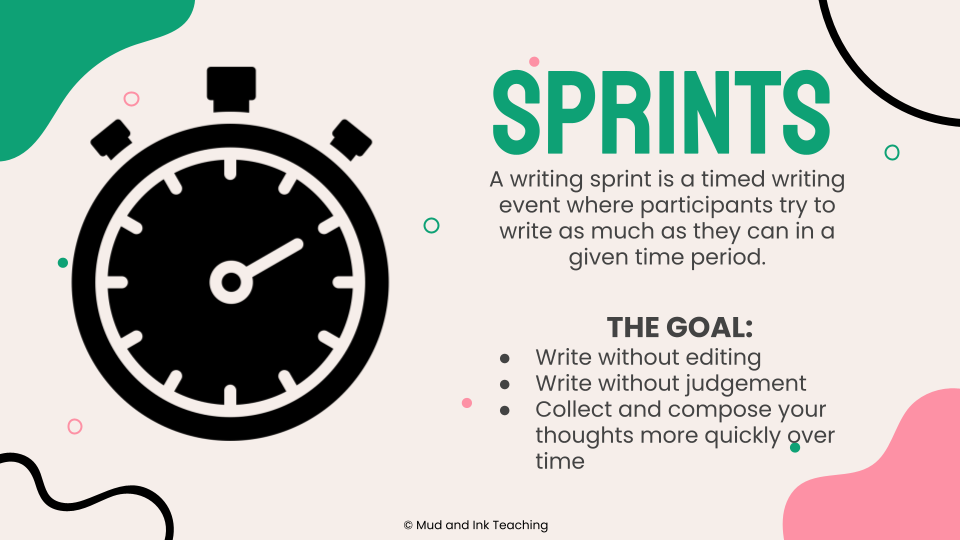

Writing Sprints

It takes practice for students to begin trusting the composing side of their brains, and making space for that regular practice is vitally important. Writing Sprints is a strategy that puts students in a position to free write under the urgent watch of a countdown timer. While this may sound stress inducing on the surface, I remind my students that not all stress is bad stress. Writing under pressure is a skill that can be learned, and it can be a huge asset to their educational and professional careers. When I set up writing sprints, they can be for a random bell ringer type writing prompt (check out these) or I might write prompts that help them start writing toward a more formal assignment. Either way, put a short countdown timer on and instruct students to start typing / writing and not stop until the timer goes off. Everything goes on the page no matter how off track, unrelated, or grammatically horrendous it is. When time is up, students can:

Read their work to a partner

File it in their binders / digital spaces

Throw it away

Keep it as a draft for an upcoming writing assignment

What matters in writing sprints is A) the physical experience of getting words on the page without stopping to overcorrect or “do something the right way” and B) the reflections on the experience afterward. Walk your students through a bit of reflection asking questions like:

How hard was it to get started today?

At what point did you feel the most uncomfortable? Why?

How much of what you wrote is usable?

How much is your brain getting things out of the way for your actual thoughts?

(after doing this a few times) How is this practice changing you as a writer?

Draft Deadlines

One way that I’ve not only helped students discover the two sides of their writing brain but also successfully gotten more work from more students is by using at least two deadlines in the writing process. The first deadline is the Composition Due Date. This is the date that EVERYONE submits their compositions unedited. I have zero expectations for editing, grammar, style, etc. This is difficult…like cringingly difficult. But, it’s also magical. There’s something so freeing for students to be told “Give me what you have in whatever state it’s in. I just want to see your brain on paper.” This is comforting, encouraging messaging that creates a culture of writing to explore and think rather than a culture of always knowing the “right” answers.

After collecting their Compositon Drafts, I read through everyone’s work and provide whole class feedback. I flag certain papers that would most benefit from 1v1 conferencing (although if there’s time, it’s great to do this with everyone!), and we then transition into the Edited Draft. This is the second iteration of the writing and this writing phase is the longest. Sometimes, students are editing their papers for up to two weeks. This looks different in everyone’s classroom, but for me, we make this a daily, timed routine AND a homework expectation. So, during the Edited Draft phase, we’ll spend 10-15 minutes per day working on editing and revising as bell work or end of class work. Once the Edited Draft deadline arrives, collect this draft and score again. If needed, individual students can continue on to another Edited Draft round, but at that point the class time has been phased out and they’re working on the continued revisions independently.

Here’s a pro tip: always give MORE time for the Edited Draft than for the Composition Draft. In fact, from prompt assignment to Composition Draft due date, I usually only give about four days: one day to sort out the claim, one day to scour for evidence, one day to dabble with an outline, and the fourth to write. Maybe there’s one more day to write, but that Compisition Draft comes in quickly. I don’t want students stuck over thinking OR procrastinating.

The Editor-Side of the Writing Brain

The editor-side of our writing brains is it’s own vibe (as the kids would say). Careful, intentional sentence structure, accurate grammatical constructs: it’s all very overwhelming for the average raised-on-autocorrect student in this generation. We can assume students have had mixed experiences with grammar instruction in their past and that with you they might be relearning or learning certain things for the very first time. This means we need to level our expectations. We need to remember that a student’s use of the lowercase “i” is not a personal attack on us as educators. Is it infuriating? Yes. But if the ideas are there and students are feeling empowered to think for themselves and try expressing that in writing? I think I can step back and reframe my approach a bit.

When I teach students about the editor-side of their brains, we talk not about “correctness” but about “accuracy”. Using the word “accuracy” has shifted the way students think about their writing. Now, with a composition in hand, have their words, punctuation, and structure accurately reflected their intention? Did they want to sound juvenile in that sentence? Was that really supposed to be a question or a declaration? When students think about editing as a mission to accurately represent themselves, the threat of perfection and correctness fades away. Students resonate with the idea of being editors with the rapid rise of short-form video content all across social media. They are editing pictures of themselves, dance videos of their friends, and even editing what they say and how they say it to the various audiences in their lives. Here are two ways to explore and teach the editor-side of the writing brain:

Rubric Box Revision

If you are practicing my Composition Draft deadline and Edited Draft deadline, then you’re probably wondering what those transition days in between look like. When I return Composition Drafts back to students, I spend that class period providing whole class feedback. Once that lesson is complete and students have examined their rubrics, their job is to pick one “rubric box” to focus on for their Edited Draft.

A few key things are happening here:

The rubric is actively providing feedback: my whole class feedback lesson is based on the things that did and did not happen according to that rubric, and the students are honing in on moving their writing from one box to the next. The rubric is performing as the tool it’s supposed to be performing.

The editing and revision is focused: students are not tackling the whole paper all at once. They’re focusing in on their evidence selection OR their commentary OR their claim OR their grammar and mechanics issues. They can focus wherever the rubric showed them their greatest area of need.

Students are directed to consider their writing by categorical skills rather than an “overall” set of points of letter grade.

need a place to get started with your rubric?

Peer Review Post-Its

Once Edited Drafts are in a stage to be resubmitted, I like to have students do some peer review. I’m not a huge fan of peer-editing, as typically peers are pretty terrible editors and it becomes way more work for me anyway, but peer revision and peer review are highly valuable. To do this, I have all students print out a physical copy of their writing and get rid of their names (I usually have them replace their names with ID numbers or coded nicknames). I then collect all of the papers and redistribute them so that everyone in class has someone else’s paper to look at.

For each round, students are given three post-it notes. On the post-it, one note has a star, another with a question mark, and the other with a happy face. After a timed silent reading period for everyone to read each other’s work, students use their three post-its to provide their feedback.

Star Post-It: Find the place in the writing where you were the most “wow-ed”. What is this students’ best line? Their most insightful remark? Write down why it struck you and how it made you stop in your tracks.

Question Mark Post-It: Find a place in the student’s writing that could use further clarification. What here is unclear? How did you read it, and what do you think the student possibly meant instead?

Smiley Face Post-It: Find a place in the student’s work where you them demonstrating a clear attempt to showcase a writing technique that we’re working on in class. Maybe it’s the claim, the embedded evidence, the commentary, or a transition statement. Point it out and comment on how they’re getting the hang of it!

It all comes down to this. Teaching writing and being a student of writing is hard. It’s complicated. It’s layered. And in order to truly tackle that complexity and create an environment where students are relaxed enough to experiment and committed enough to grow, we must carefully consider the ways in which we create writing experiences for our students. Providing opportunities to write for pleasure, experimentation, and exploration are key, but so are the opportunities to develop voice and practice the smaller, more mechanical side of writing that will accurately help students share that voice with others.

SPOTLIGHT RESOURCE:

If you’re ready to assign get started with a great rubric, my Literary Analysis Starter Kit is a go-to resource for hundreds of teachers. Check it out here!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amanda is the author of Mud and Ink Teaching and a collaborative blogger on Teachwriting.org.

A high school English teacher of every level from ESL to AP Language, Amanda has made it her life’s work to encourage students and teachers to join her on an adventurous teaching and learning journey. Amanda is a full-time teacher author after spending thirteen years in the classroom. She writes curriculum for the high school level, coaches teachers 1:1, and travels with her family whenever possible. Amanda’s obsessed with poetry, argumentation, and showing students the power of taking chances in their writing. She is also the co-host of the podcast Brave New Teaching.

Visit Amanda on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter for English teacher inspiration and powerful community.