Engage Students in Analyzing, Revising, and Writing Effective Sentences with these 6 Steps [Examples of Incomplete Sentences, Complete Sentences, and Run-ons Included]

Many students have never been explicitly taught how to write a complete sentence. In secondary classrooms, it is a common mistake to assume students already have this skill and are prepared for the challenging academic writing we expect of them.

When we make this assumption and don't make time to teach about complete sentences explicitly, the result is pervasive run-on sentences and writing that includes lots of words but no punctuation and not one capital letter!

Teachers often complain students write like they are texting, and their sentences are missing subjects or a complete idea. In this blog post, I'll take you through a simple six step process for getting students to not only write complete sentences but have variety in the kinds of complete sentences they utilize.

Step 1: Analyze Mentor Sentences

A mentor sentence is any quality sentence that can be used to help students understand and utilize a literary or grammatical concept in their own writing. The English language is complex and in order to become adept at utilizing words in an articulate way, students need to be exposed to lots of writing!

Start by showing students examples of incomplete sentences or what I like to call "purposeful fragments" in literature. In addition, show students examples of complete sentences in literature.

Be sure not to define these as incomplete or complete though!

The reason for this is described in step two. The whole point of the first step is to just look at the sentences and discuss observations.

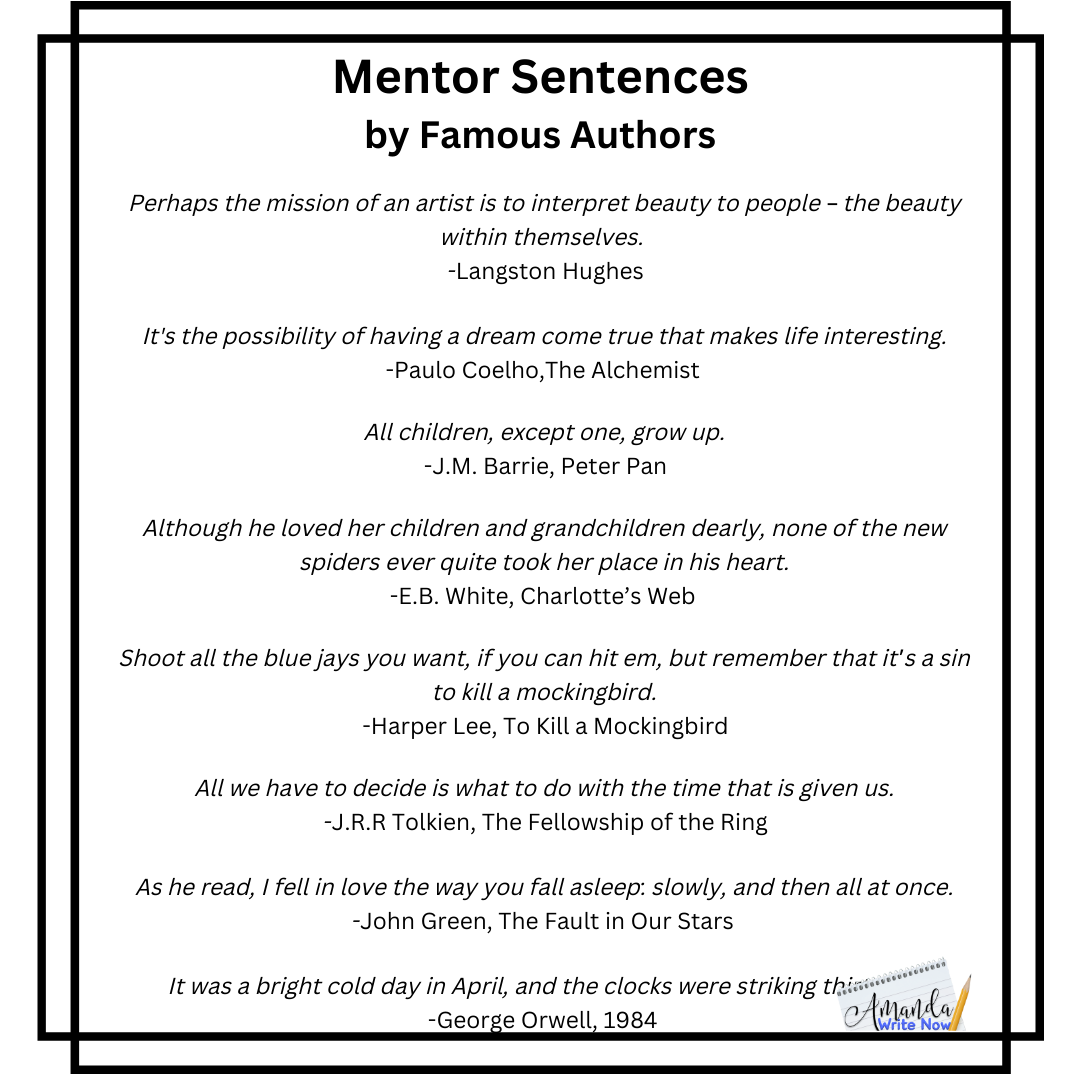

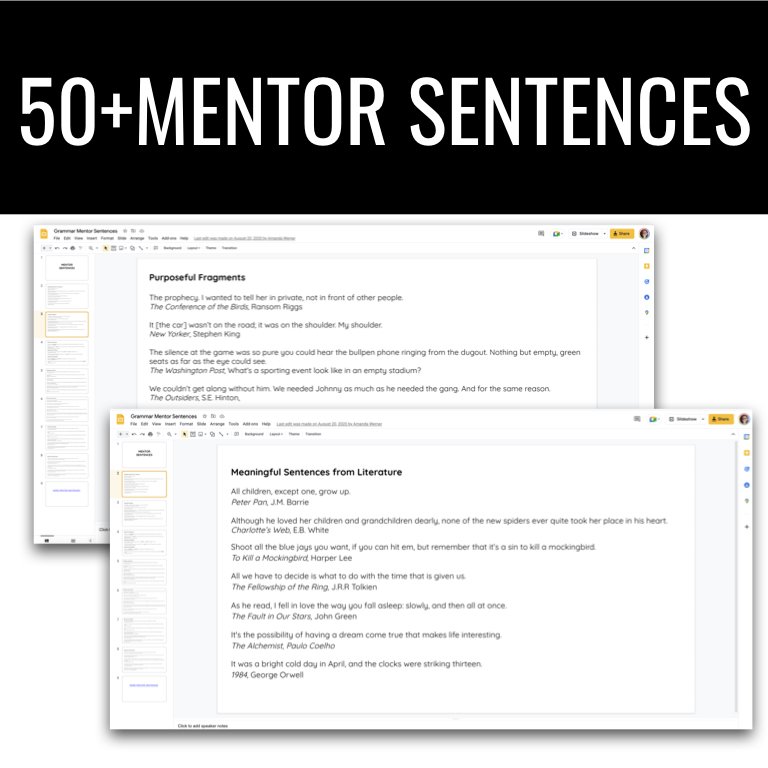

To the right is an image with lots of mentor sentence examples from famous authors. These sentences are all examples of complete sentences. They include sentences with a variety of grammatical structures. We want students to be exposed to longer sentences and shorter sentences, fragments, and complete sentences. The easiest way to find your own mentor sentences is by looking through your favorite books. If you are trying to teach students how to use commas, how to identify a subordinate clause, coordinating conjunction, or identify the main verb of a sentence, all of these grammar concepts can be found in any book you read. The first sentence is one of my favorites:)

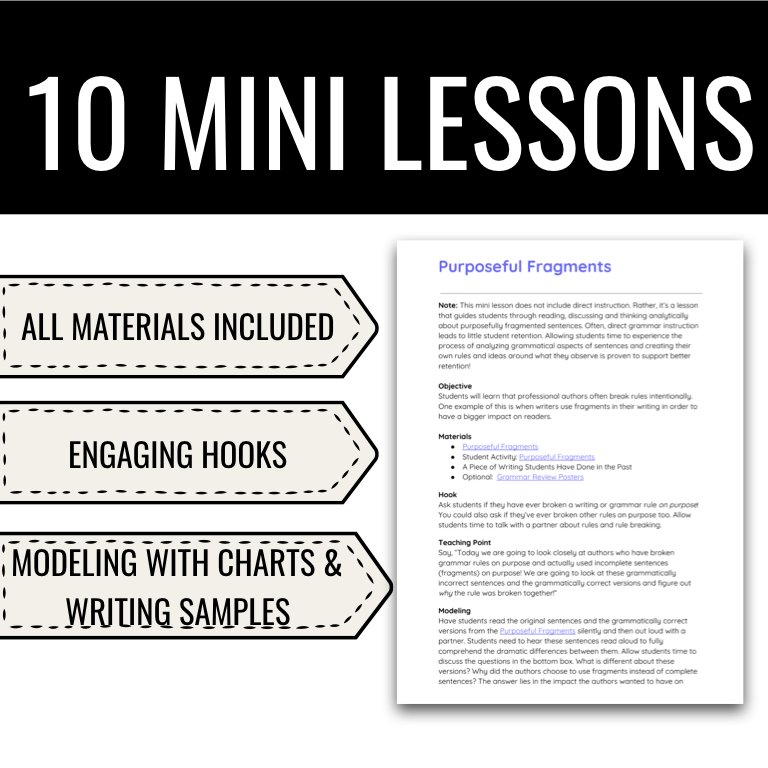

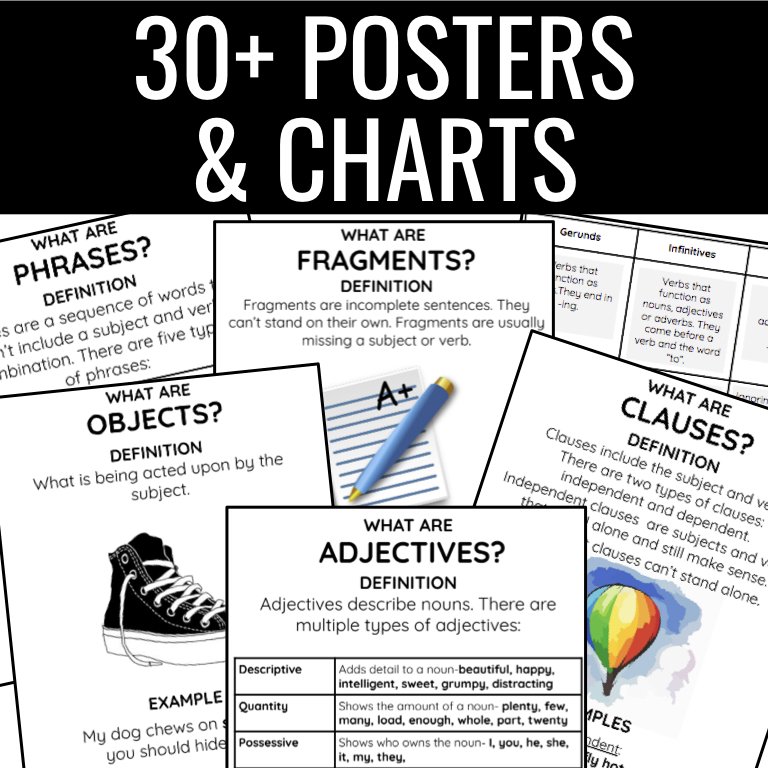

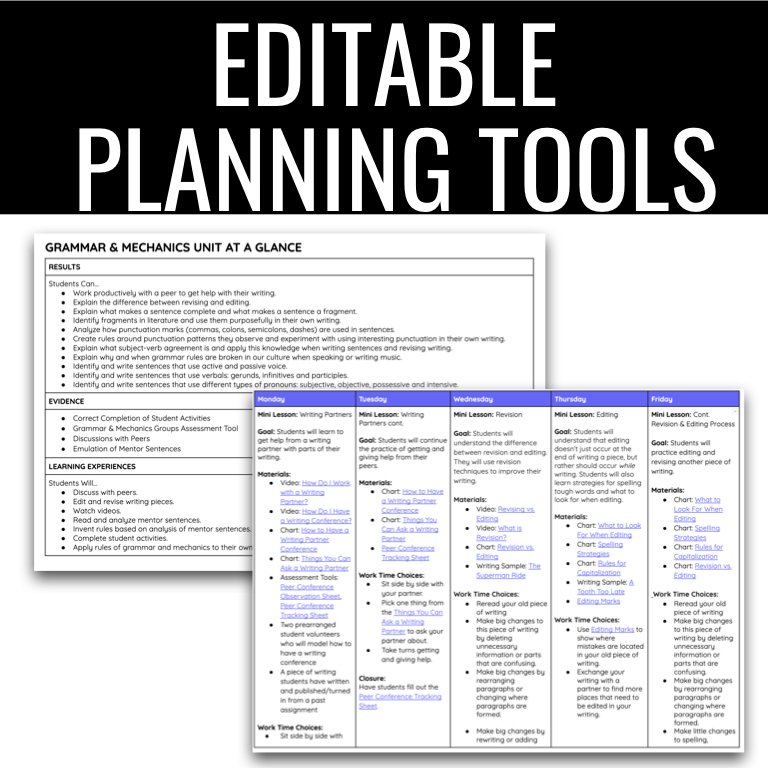

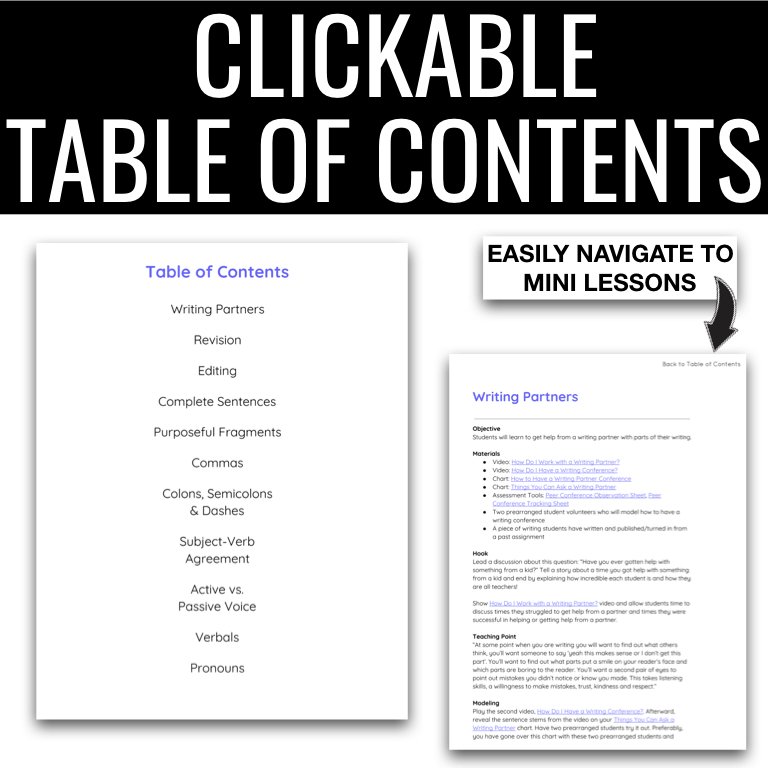

Want a ton more mentor sentences as well as mini lessons that are engaging and fun for students. Check out this comprehensive Grammar and Mechanics Unit:

Step 2: Define What Makes a Sentence Complete

Rather than teaching all sorts of grammatical terms, or the parts of a sentence, allow students to come up with their own definition of a complete sentence. Accept all definitions students come up with and try hard not to start teaching technical, grammatical terms (don't worry you will have time for that in the last step!).

After students have written their definitions down, have student volunteers share their definitions. Try to get students to elaborate on what they mean if they use terms in their definition such as subject, verb, independent clause, dependent clause, subordinating conjunction, or action verb. Explain to students that we really want our definition to be as clear as possible, so we don't want to use too many technical grammar terms. Also, some students can feel overwhelmed if we bombard them with too many grammatical terms. Grammar is best done within the context of reading and writing and studies have shown this to be true!

Finally, combine the definitions into one class definition. We want this definition to go beyond a sentence being a group of words. A class definition of a complete sentence without too many grammatical terms might go something like this:

We know a complete sentence must have:

a capital letter at the beginning

a punctuation mark at the end

it must make sense when it stands alone

it must include a person, place, or thing (or a word that can stand for the person, place, or thing)

it must include some sort of action

Notice this definition doesn't really include technical grammar terms! There are many different ways to approach helping students write complete sentences, but the most engaging way is to allow students to come to conclusions on their own about what a complete sentence is.

Step 3: Identify Run-on Sentences

Now that students have a working definition of a complete sentence you'll want to show students examples of sentences that run on. Ask students what they notice, discuss these sentences, refer back to your definition of a complete sentence, and ask if the run-on meets all the requirements of a complete sentence. revise your definition of a complete sentence to include something about not letting a sentence go on and on.

The following sentence is an example of a run-on:

My teacher put the tooth in a plastic bag and I put it inside my desk I stuffed it inside carelessly with other books and supplies.

Explain to students that this sentence does meet all the requirements to be a complete sentence but there's something wrong with it. Have students try to explain what seems to be wrong and how it might be revised. Introduce the term run-on sentence and add something about run-ons to your definition of a complete sentence. You might add to your definition like the last bullet in this list:

We know a complete sentence must have:

a capital letter at the beginning

a punctuation mark at the end

it must make sense when it stands alone

it must include a person, place, or thing (or a word that can stand for the person, place, or thing)

it must include some sort of action

it can't go on and on and on or it will be hard to read and understand

Step 4: Identify Examples and Non-Examples

After you have a fully formed definition of what a complete sentence actually is, you're ready for students to start using the class definition to identify examples and non-examples. It's fun for students to take on the rule of incomplete sentence checker! The teacher isn't the only one who can identify mistakes. It's also important to demonstrate how famous authors break grammar rules too! Students are often surprised that famous authors use writing fragments!

Here is an example of a fragment (the fragment is underlined) you could discuss with your students that's by a very famous author:

We couldn’t get along without him. We needed Johnny as much as he needed the gang. And for the same reason.

-S.E. Hinton, The Outsiders

Now, have the class test the fragment with your definition of a complete sentence. The underlined fragment is not a complete thought, it's a great example of an incomplete sentence. It doesn't have any sort of action, however, it does include a thing: "reason". It would definitely make not make sense standing alone, it's missing information. Have students say the fragment out loud. Ask your class, would this fragment make sense if you walked up to a stranger on the street and said it out loud to them? No, it wouldn't. The preceding main clause is the only thing that allows this fragment to make sense. But, this fragment was put there for a reason: emphasis. Now, show the mentor sentence revised into a complete sentence:

We needed Johnny as much as he needed the game and for the same reason.

This sentence is not as powerful as the actual sentence that S.E. Hinton used in her book. Students benefit greatly from analyzing complete sentences in literature and incomplete sentences (a kind of fragment). Students also benefit from creating their own definition of what a complete sentence is and then testing that definition out on different mentor sentences (fragments and complete).

Step 5: Revise Sentences in Their Writing

Next, you'll want students to read over writing they've done in the past and apply what they've learned. Have students highlight the following in different colors: complete sentences, purposeful fragments (if they choose to use them for emphasis), and long sentences.

Ask for any student volunteers who would be willing to share any long sentences they found in their writing. Boost these student volunteers' self-esteem by explaining that it's important to have both long sentences and short sentences in writing. Praise these students for their hard work! Explain that having both long and short sentences is called having sentence variety. We want to boost self-esteem before analyzing and revising the volunteers' sentences together as a class.

As a class look at the long sentences shared by volunteers and get opinions about if they think it's a run-on or not. Remember this should be a collaborative effort by the class. If the longer sentence has been deemed a run-on, collaborate with the class about different ways the run-on might be revised. You might use a comma, semi-colon, or colon, or break the sentence into two or even three separate sentences. It's important you model all the many ways that a sentence can be revised!

Step 6: Teach the Grammatical Terms

It can be helpful to teach grammatical terms after lots of time spent analyzing mentor sentences and having students define what complete and incomplete sentences are for themselves. Allowing students to take ownership of grammar and teaching within the context of writing is the best way to help students retain this information.

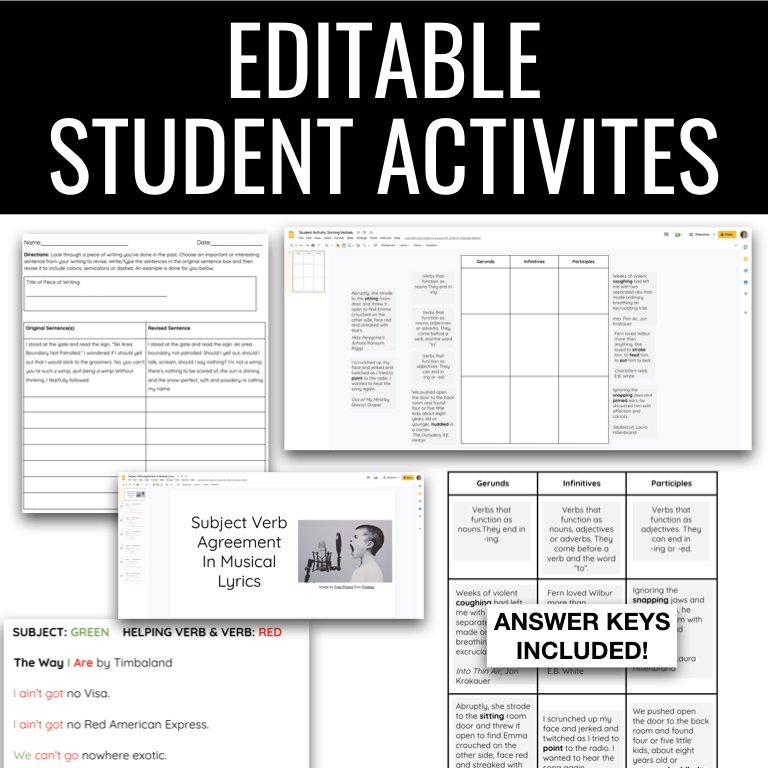

I recommend teaching the following grammar terms after following steps one through five: subject, verb, object, independent clause, dependent clause, and predicate. I wouldn't teach all of these terms in one day though! Instead take a day to teach each, using mentor sentences. Allow students time to identify the grammar term in their own writing by highlighting examples. Students might even share examples of sentence fragments they have purposefully used for emphasis!

Wrap Up

Many teachers find teaching grammar daunting, myself included! But, it doesn't have to be that way. The best thing about teaching grammar is incorporating our students' voices, opinions, definitions, and input. The more you can include students in the process of learning about the pieces of sentences, the better!

Related Resources

Complete Sentences Mini Lesson

Related Articles

Simple Ways to Empower Young Authors with Grammar

Grammar Games for the Secondary Classroom

Using Mentor Texts to Teach Writing

About the Author

Amanda Werner has been teaching for 14 years and still feels like a novice. Every year is a unique and exciting challenge to inspire a new group of students to become avid readers and writers. Amanda reads educational literature voraciously and writes about the teaching of reading and writing on her website amandawritenow.com. Amanda received her B.A. in English Literature with an emphasis in Humanities at Western Washington University. In her free time, Amanda loves being outdoors with her husband and daughter.